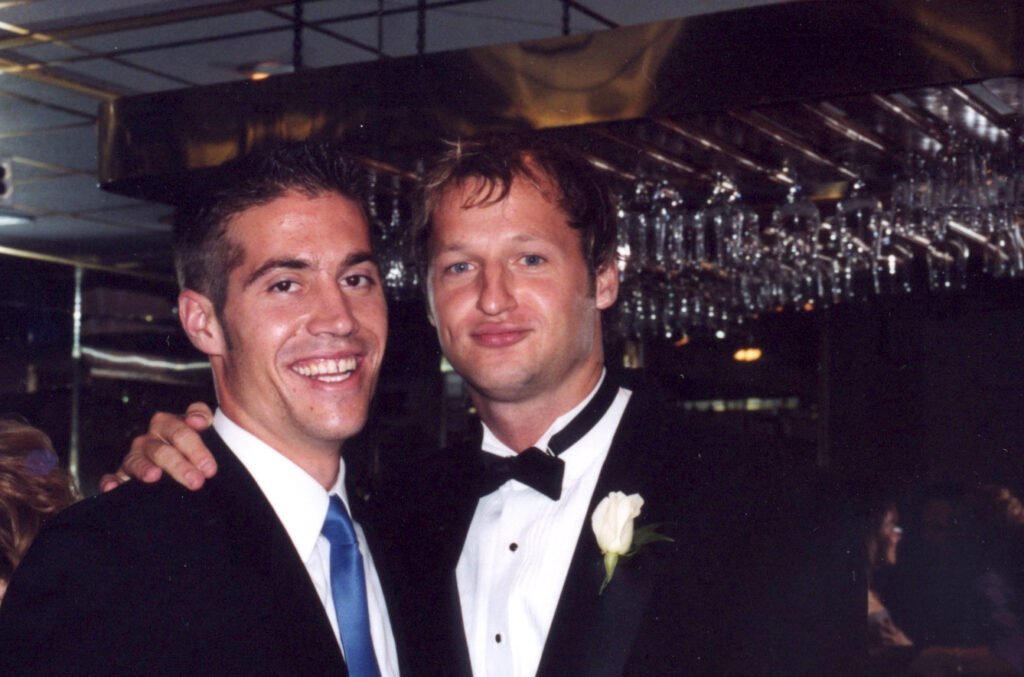

In his second collection—a powerful act of documentary poetics a decade in the making—Johnson chronicles the perils and joys of fatherhood and a shattering tragedy that plays out thousands of miles away. Nearly two years after the poet’s closest friend went missing, journalist James Foley was executed by ISIS in Syria. In this poetic daybook like no other, Johnson often speaks directly to his missing friend—“I don’t know, Jim, where you are,” even long after his death. Page to page, Foley ghosts in and out of the book, as the poet hails the birth of children, recounts hunting for the body of a neighbor’s missing cat, and, later, pores over the hand-written pages that Foley smuggled out of a Libyan prison in his shoe. An educator and poet, Johnson has crafted a vibrant, urgent collection that pulses with the terror and hardship Foley faced, the anguish of those he left behind, and the everlasting friendship between the two men. During a time of great collective trauma and mourning, this heartfelt, formally rich collection tackles the question: “How do you go on living, loving, and creating in the face of unthinkable loss?”

Purchase Now

Missing

There, then not. A late summer whiff of something gone. It depended on the wind. I checked the trash, after Ebele asked— no maggots, no rancid fat globbing the bin’s lid—hunted through bushes, bellied under the latticed front porch. Tuesday, Wednesday: 85, 90 degrees. The stink massive. A squirrel, a raccoon? Too rank to be a chickadee wind-swept from its nest. My panic grew. Now, I think I know why. I waded into shoulder-high hydrangeas, greened with blooms, parted the branches—a blue plastic bag, beer bottle cap, a skull-shaped rock. Then I saw it—a patch of white, matted there, sticks piercing the spongy form. I covered my mouth & nose, retreated to the bulkhead for leather gloves, a bandana, & a small coal shovel. As I worked, I made out hind legs, splayed, the orange & white marbled fur—carrion beetles writhed, quaking, once more, the belly of my neighbor’s cat. What do I do with the body? I asked Ebele. This was the cat that leapt from a tree onto the roof of the red Colonial on Delano & survived for weeks, eluding firemen who telescoped their ladder out, this the cat, while I sat at my desk each morning to write, that padded down the front steps of my elderly neighbor’s house, jumped the chainlink & crossed the boulevard, stepping between magnolias. Your calico cat, I fear, has died in my hydrangea bush, I started the letter to my bed-ridden neighbor. Though we needed to get rid of the body, though the heat thickened & soured, I spent hours laying down my words, striking, double-striking them, starting, again. This, I needed to get right.

Inshallah

-for Diane & John Foley

When it was over, though it would never be over, Jim’s mom sent a gift to our house, a chrome lamp & candles, a tornado lantern or hurricane lamp. It depends what you call that black wall of water, skirling & rising, that takes what it wants: cars, refrigerators, cows, wedding photos, birth records— inshallah— your firstborn son. When it was over, though it would never be over, as it would never be before again, only after, as the rains, the rains would never be the same rains or lashing waves— I struck a match against the flooding dusk, then, again, & hung the lamp.

In The Press

“The moment when Jim was captured and went missing changed me, and everyone knew knew him, on a molecular level.”

Daniel Johnson, Poetry Off the Shelf Podcast: Falling off the Stairs

&

“My chest tightened. My mind seized. I could barely choke out the words. This wasn’t ordinary stage fright. It was something deeper, much rawer. My body and mind were reacting as if I’d just viewed the video of Jim’s execution, again.”

Accounting for the Unaccountable: Daniel Johnson on Writing about His Friend, James Foley at Literary Hub

Huffington Post: A Poet Remembers Journalist James Foley

McSweeney’s Press: Short Conversations with Poets

I don’t know that poetry has helped me understand or accept Jim’s death—nothing could probably do that—but I’ve been able to speak to Jim, to ask him questions, to spend my winter mornings with him, despite his long absence.

Daniel Johnson, McSweeney’s Press